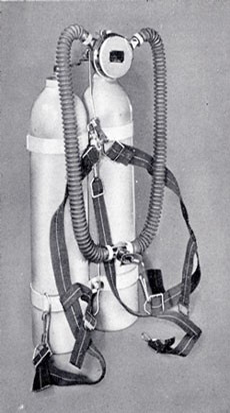

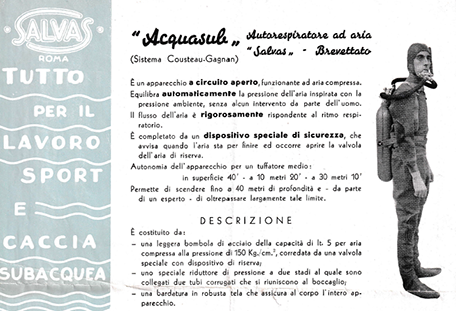

If you ask aged divers which was the first SCUBA model available in Italy, most of them will answer: "the Mistral of course!". Few of the most informed ones could answer the Explorer or perhaps the Tricheco both produced by Pirelli but only very few, among the eldest ones and already active as divers after the mid-1950s, will know that the first SCUBA apparatus marketed in Italy, starting from 1954, was the "Acquasub" by the Salvas company of Rome (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

|

|

| fig. 1 | fig. 2 |

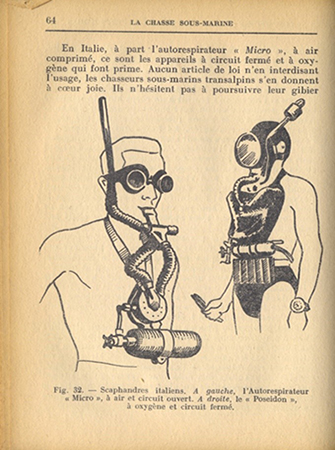

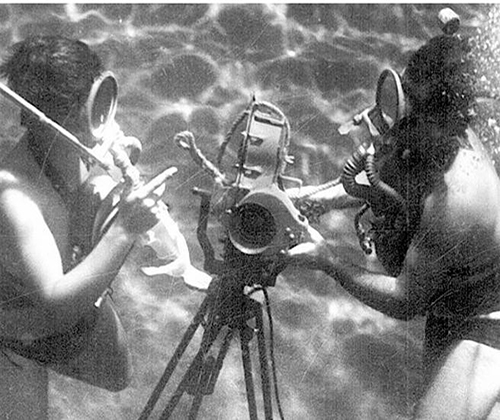

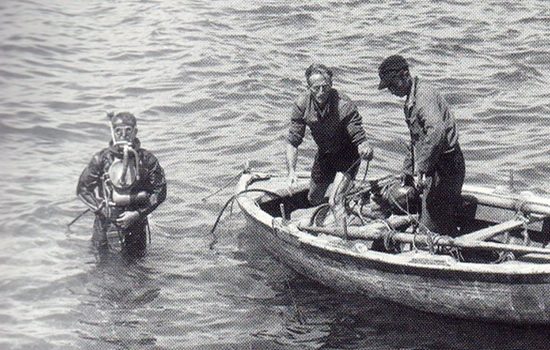

Really, in the years immediately following the end of the Second World War there were some special applications of compressed air breathing diving equipment which, in addition to never reaching significant production volumes, did not receive any commercial promotion. Traces of these devices are found only in some old publications and books and, above all, because the use of these devices remained associated with some particularly important events that occurred in that specific historical period. Unfortunately, there is no physical evidence of these devices as we do not know that there are still samples preserved in museums or owned by collectors of diving equipment.We will therefore try to best describe them based on the scarce documentation available.One of these models, called "Micro" is mentioned in the 1954 edition of Dr. Gilbert Doukan's book "La Chasse Sous-Marine" (see Figure 3 and Figure 4).Having never heard of this device, of which the manufacturer is not even mentioned in the book, we tried to understand if there were traces or some type of documentation that could provide us with other useful information. Then we remembered that, in our previous article on Italian oxygen rebreathers (A.R.O.), a strange device was mentioned (see Figure 5) still produced by Salvas and used by Prince Francesco Alliata of Villafranca, one of the first Italian pioneers of scuba diving, as well as film producer in the 40s and 50s, during the underwater video shooting of the film "Vulcano" by director William Dieterle starring Anna Magnani, Geraldine Brooks and Rossano Brazzi, shot in 1949 between Sicily and the Aeolian Islands (see Figure 6).

|

|

| fig. 3 | fig. 4 |

|

|

| fig. 5 | fig. 6 |

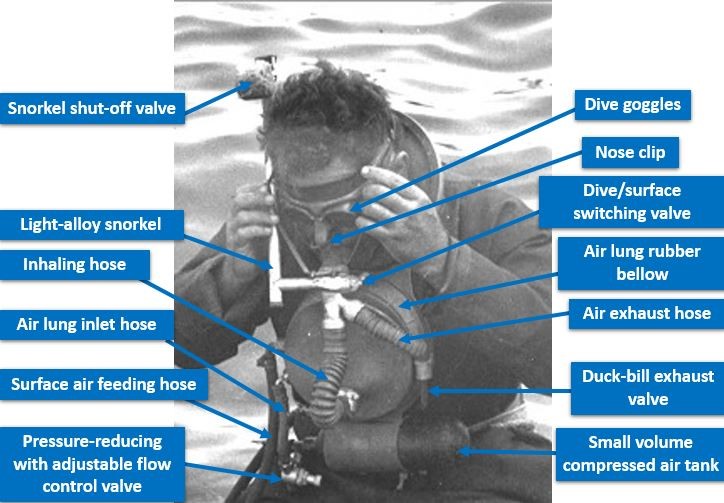

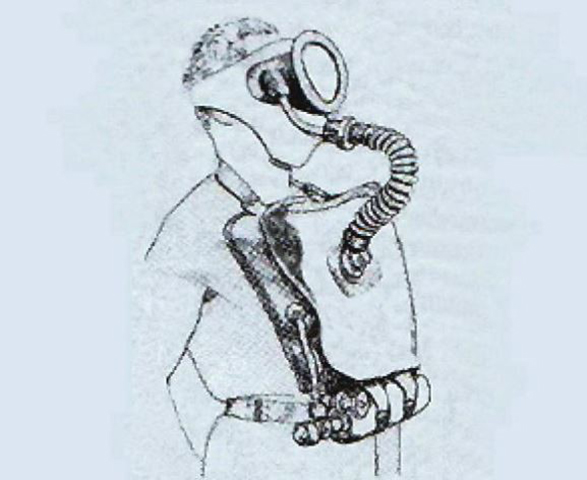

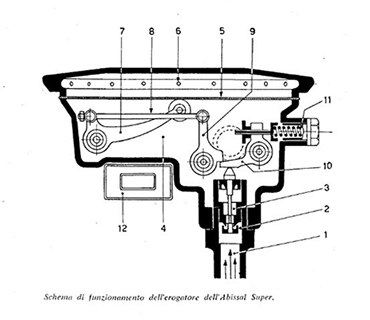

This device, which could be used indifferently in SCUBA configuration or with surface air supply (Hookah), is described in its main elements in Figure 7.

|

| fig. 7 |

In the film, in addition of being used in Hookah mode (see Figure 8) by Alliata, who wore goggles and nose clips as shown in the aforementioned book, during all underwater shooting, it was also used, this time in SCUBA mode and wearing a diving mask (see Figure 9), by one of the two protagonists of the underwater combat shown in the film.

|

|

| fig. 8 | fig. 9 |

The evolution of this underwater breathing apparatus, from the model used during the shooting of the film "Vulcano" to the one depicted in the book "La Chasse Sous-Marine", would seem to consist in the replacement of the rubber bellows lung with a pressure reducing device similar to that used in the first double hose regulators of that period.

This device was certainly not designed and produced by Salvas specifically for the video shooting of the film "Vulcano" but it was one of the tools conceived in the years immediately after the war, especially for works in the shallow water, necessary for demining and removal of wrecks in the harbors areas. It was noted that the use of devices like this, or of oxygen rebreathers (A.R.O.) when the maximum working depth allowed its safe application, was much faster and cheaper than that of traditional "hard hat divers".

A similar device of which we have found very few traces is the underwater breathing apparatus model C. F. 69 produced by Cressi since 1947 (see Figure 10 and Figure 11).

|

|

| fig. 10 | fig. 11 |

Cressi derived this air model using the most important components of the AR47 oxygen rebreather model (lung bag, harnesses, cylinders, corrugated hose between lung and mouthpiece, full-face mask). The components specifically designed for this application were the cylinder valve, which allowed the connection with the air feeding hose coming from the surface, the connection plate between the lung and the corrugated hose, which did not include the use of the soda lime canister, and the special mouthpiece that integrated on the right side also the short hose for the discharge of exhaled air and the necessary one-way valves. In this case, as it was for the "Micro" predecessor, the lung bag maintained the sole function of balancing the pressure of the air inspired by the diver with that of the external environment. The other task that the lung bag had when used in AROs, namely that of containing a minimum volume of oxygen for a complete breathing cycle, a volume to be constantly purified and cyclically restored as a results of the body's metabolic consumption, in this case was no longer necessary.

After the period of port works and coastal demining, the production of these devices came to a halt due to the collapse in demand and the complete absence of a sports-recreational user market. Even a few years later, when the first Cousteau-Gagnan type self-contained breathing apparatus appeared, these devices with ventral-type lung bags were never competitive compared to the Cousteau-Gagnan ones, especially due to their very low autonomy when used in SCUBA mode. The application of ventral cylinders of much higher capacity, which would have been necessary to drastically increase the autonomy of the device when used in SCUBA mode, brought limitations not easily compatible with an ease use of the device and an effective underwater buoyancy.

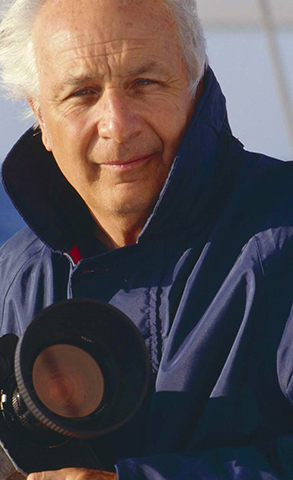

Therefore, even if virtually the devices described above were really the first underwater air breathing devices appeared in Italy, the first model that had a real phase of mass production and marketing to an audience of sport divers was the Acquasub by Salvas. The history of this regulator is little known but, nevertheless, it is very fascinating because it is associated with very important and significant events at the dawn of diving in Italy, as well as with the main achievements of some great pioneers of our country. In particular, the person who baptized this device and who followed all its developments, from the prototype phase to the production exit, was Raimondo Bucher, a great Italian diving pioneer and whose name has remained associated with numerous events having him as the protagonist, from the period immediately before the Second World War up to the 1960s.

For those who do not yet know the famous "commander" Bucher, here is a brief summary of his life. Born in Hungary from an Italian father and Austrian mother on March 15, 1912, he entered the Regia Aeronautica (the Italian Royal Air Force) starting from 1932 as a pilot officer, participating in the Second World War and finally taking leave with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, after thirty years of service.

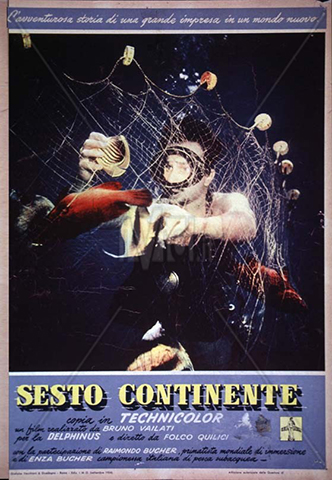

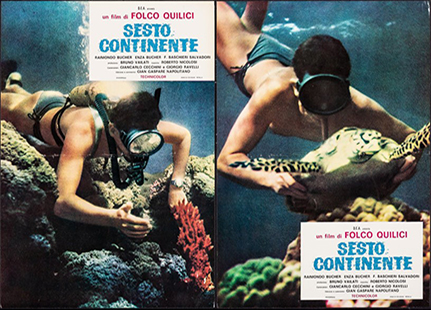

He began his career as a spearfishing diver and soon distinguished himself at the highest level by winning two Italian spearfishing championships in 1951 and 1952 and becoming a freediving record holder with -30 meters in 1950 and then with -39 meters in 1952. And right between the end of 1952 and the summer of 1953 he participated, as head of the sports group, to the famous Italian National Expedition in the Red Sea, organized by Bruno Vailati at the Dahlak islands in Eritrea. From this experience Sesto Continente, the first underwater full color feature film, directed by Folco Quilici, was made (see Figure 12 and Figure 13).

He was also one of the pioneers of underwater photography, inventing, experimenting, building cases and diving housings of all kinds. It is said that he was the first to introduce the use of the o-ring in the construction of underwater housings in Italy, having seen its use in the landing gears of some American fighters of the Second World War.

Having concluded his competitive experience in the mid-1950s, he devoted himself to countless undertakings including the discovery and exploration of the submerged city of Baia, the exploration of the underground stretch of the Bussento river, as well as of some submerged caves in Capri island and the Bue Marino cave in Sardinia. It was then the protagonist of the red coral harvest in Sardinia for most of the 60s and 70s. He continued to dive even after the nineties, always making his voice heard in defense of the sea against building speculation, pollution and indiscriminate fishing. He died in Rome on 9 September 2008.

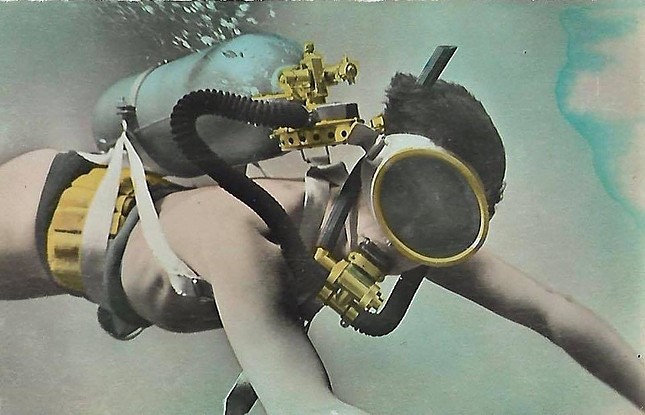

We need to remember that the modern self-contained breathing apparatus (SCUBA) was invented by Commander Jacques Y. Cousteau and by Engineer Emile Gagnan in 1943 (see Figure 14 and Figure 15) but it did not appear on the market before 1946 when the French group Air Liquide, for which both Gagnan and Cousteau's father-in-law worked, this latter as a member of the Board of Directors, founded La Spirotechnique company.

The self-contained breathing apparatus, called CG-45 from the initials of the inventors and from the year when the patent was filed, consisted of a double pressure reduction stage, integrated into a metal body having the size of a mechanical alarm clock, of two separate corrugated hoses for the inspiration and for the expiration flows and of a “T” shaped mouthpiece. The device also included the high-pressure cylinders (with variable volumes and quantities depending on the autonomy required), the pipes and the tanks valve for connection to the regulator and finally the harness to be worn by the diver (see Figure 16 and Figure 17). Unfortunately, despite the efforts and investments made by the French company to increase sales of this device, the demands of the domestic market alone were limited also because at the time the practice of scuba diving using self-contained breathing apparatus was practically unknown to the general public. Most of the requests came from the military and professional sectors, which, however, were certainly not enough to satisfy the commercial ambitions of the French company and of Cousteau himself, who was its President.v

|

|

| fig. 12 | fig. 13 |

|

|

| fig. 14 | fig. 15 |

It was therefore a question of expanding the sale of these equipment even beyond the national borders and, above all, of creating a sports-recreational market that did not yet exist in the world. The few sport divers of the time were basically spearfishing hunters and it was therefore necessary to present the new device as an instrument that could dramatically improve their hunting performances, thanks to the greater diving autonomy that was guaranteed.

|

|

| fig. 16 | fig, 17 |

But above all it was necessary to find an effective means of communication that could show the great potential of the new device and reach millions of potential customers all over the world. And the solution came thanks to the cinema and television which in those years were beginning to spread as the main communication media.

And this was precisely the winning experience achieved in the North American market with the establishment of a very powerful sales and distribution network (the U.S. Divers) and with the incredible advertising effects offered by cinema and television that were becoming increasingly interested in the new sport.

What was happening in Italy in the same years? Off course, the appearance on the main international markets of this new device had not gone unnoticed by the very few small or large companies already present in the Italian diving equipment market who, in the early 1950s, were only Pirelli, Cressi and Salvas. But apart Cressi, which from the beginning had dedicated itself to the sports market and in particular to that of spearfishing, Pirelli and Salvas were struggling to find a sustainable commercial target considering that their main market had been, until the end of the Second World War, the military one. With most of the military orders declining after the war, the two companies mentioned above had to somehow reconvert and find a different commercial target than the traditional one.

Cressi had already made its choice in 1947: for the Genoese company, self-contained-breathing-apparatus meant A.R.O. or oxygen rebreather, in the wake of the experience gained by the operators of the Human Torpedoes (better known as Pigs) and by the assault Frogmen. These experiences and knowledge would have allowed the company to develop oxygen rebreathers specifically designed for sport divers and training (the AR47 and the 57B models). The same choice was also initially made by Pirelli, which offered similar devices for recreational diving (the Poseidon and the Polifemo models).

The only company that decided to try its way by proposing the new self-contained breathing apparatus was Salvas which in 1952, taking advantage of the upcoming Italian National Expedition to the Red Sea being organized, offered itself as the sole supplier of diving equipment, hoping to get important image and advertising returns that would certainly have followed that enterprise. The prerequisites were all there since, already in the preparation phase, the initiative was attracting the attention of numerous information channels and the main media. In the same period, Salvas had already get in touch with La Spirotechnique for a possible production under license of the Cousteau-Gagnan device but was also experimenting some SCUBA devices of its own invention. The first official appearance of the Salvas SCUBA device, although still in prototype form, took place in the summer of 1952 when the entire group of participants in the expedition gathered on the island of Ponza to develop programs and equipment.

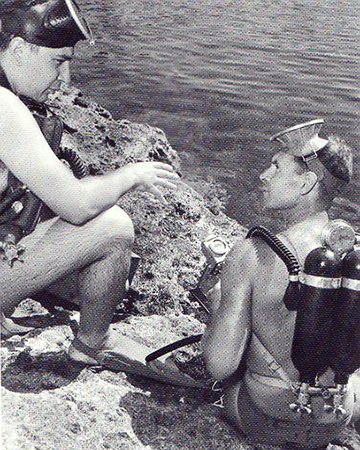

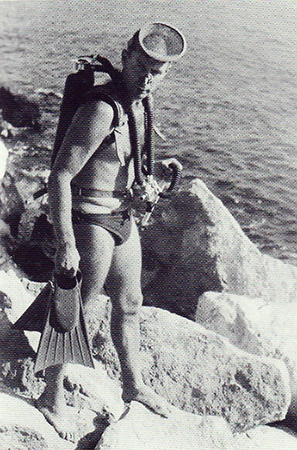

On that occasion there was the opportunity to test the various prototypes developed by Salvas, including the various accessories linked to them. In Figure 18 and Figure 19 we can see two different prototype configurations used by Bucher during the Ponza experience.

|

|

| fig. 18 | fig. 19 |

In Figure 18, which shows Bucher next to Folco Quilici, who is equipped with his faithful A.R.O., a device that he will never leave during all the underwater video shots of the Sixth Continent, the regulator body does not include the air exhaust mechanism, as in the Cousteau-Gagnan equipment. In the Salvas prototype this consisted of a corrugated tube with a duck-bill valve at the end which was fixed laterally to the tanks metal clamps and oriented downwards. The two small-volume tanks (we believe they are 2 liters each) have the valves on the bottom and a rigid pipe linking them to the regulator body.

The choice of tanks so small compared to the normal sizes that we usually see with SCUBA units should not be too surprising. We are still in 1952 and in Italy there were still no companies producing compressed gas cylinders of adequate volume for the new breathing devices. The first cylinders of greater volume (10, 12 and 15 liters) would have arrived no earlier than the mid-1950s from Dalmine (see Figure 20 and Figure 21). The 2-liter cylinders were instead available as normal equipment of the military A.R.O. rebreathers that Salvas had begun to build and market immediately after the war and which really were the same units used in the oxygen-assisted breathing systems of military aircraft.

|

|

| fig. 20 | fig. 21 |

In the configuration of Figure 19 the layout of the device is slightly different with the axis of the main body oriented upwards and the duck-bill valve directed towards the back of the diver. Here you can also see the famous Salvas mouthpiece provided with a button to switch between “dive” and “surface” mode and with the snorkel integrated directly into the mouthpiece. This solution, in the intentions of Salvas, should have been a strong element of attraction for the reference customer of this device who, as we should remember, was the spearfishing diver. The special snorkel was supposed to facilitate the search for prey, which could be done by swimming on the surface and breathing directly from the snorkel thus saving precious air. The special mouthpiece then prevented water from entering inside the corrugated hoses, thus eliminating the need for unwanted and complicated air bleeding operations. Once the prey was identified, the button could be placed in "dive" mode and the SCUBA units was perfectly ready for the descent. The first version of this special mouthpiece had the connection ducts with the corrugated hoses oriented forward by about 45 °, as seen in Figure 19. In the prototype configuration used in Ponza, the snorkel consisted of a piece of corrugated hose which was then connected to another piece of rigid pipe.

Among the various initiatives undertaken to attract the attention of the media and the interest of the public on the imminent departure of the Italian National Expedition in the Red Sea, it is certainly worth mentioning the attempt to record free diving at -39 meters that Raimondo Bucher successfully achieved in the waters of the island of Capri on November 2, 1952.

The expedition officially departed from Naples on December 26, 1952 with the small motor ship "Formica" of only 130 tons and ended, again in Naples, on June 24, 1953. In the numerous dives carried out during the expedition, depending on the objectives and depth, the group of divers alternated the use of the Acquasub SCUBA units with the Salvas A.R.O. rebreathers or simply with the snorkel equipment only (see Figure 22 and Figure 23). In Figure 22 we see Bucher just before one of these dives with the Salvas scuba unit, a Rolleiflex camera inside a diving housing and a flash with bulbs of his own invention.

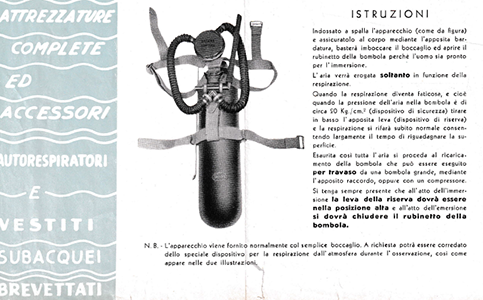

After the summer experience in Ponza but also after comparative tests between the various Salvas prototypes and the Cousteau-Gagnan device, the company decided to build the new SCUBA unit under a La Spirotechnique license. Therefore, the "Acquasub" model was born and Salvas also began to deal with the marketing phase of the device. The first advertising leaflet of the Acquasub SCUBA unit is shown in Figure 24 and Figure 25.

|

|

| fig. 22 | fig. 23 |

|

|

| fig. 24 | fig. 25 |

We believe that this leaflet is dated 1954, the year in which the production of the regulator was started. As can be seen from Figure 25, the image of the regulator identification label is still missing. This label, showing both the commercial name of unit and the Salvas logo is shown in Figure 26. In Figure 24 you can see the special mouthpiece still in its first version with the tubes oriented forward and the tank, which was available only with a volume of 5 liters and with a maximum filling pressure of 150 bar.

A specific feature of this regulator was that of the corrugated hoses which were longer than those normally used in the standard CG-45 model. We believe that this need was due to the special 45 ° forward orientation of the special mouthpiece hoses connecting ducts. Since there were no such corrugated hoses in the production of that period, Salvas obtained them by joining two shorter corrugated hoses and then by vulcanizing their connection. These connections can be easily observed in the middle of each individual corrugated hose (see Figure 1).

The special mouthpiece would then be modified by Salvas by eliminating the forward orientation as shown in Figure 27 and Figure 28.

|

|

| fig. 26 | fig. 27 |

|

|

| fig. 28 | fig. 29 |

As can be seen in Figure 28, Salvas also wanted to offer this device in a version with full-face mask. The company believed that this solution could be attractive to those potential customers who already used the oxygen rebreathers with this type of accessory, an accessory considered fundamental during operations in polluted water or as a safety measure in case of loss of consciousness experienced by the operators.

For this scope it was used the same full-face mask which was already part of the production of the company because used in the A.R.O. rebreather (Universal model) available for the military market (see Figure 29).

In order to be coupled to the Salvas full-face mask by means of a special strap, the central part of the mouthpiece facing the diver was equipped with a kind of ring that was soft welded to the body of the mouthpiece. This piece was made of marine brass and finally chromed.

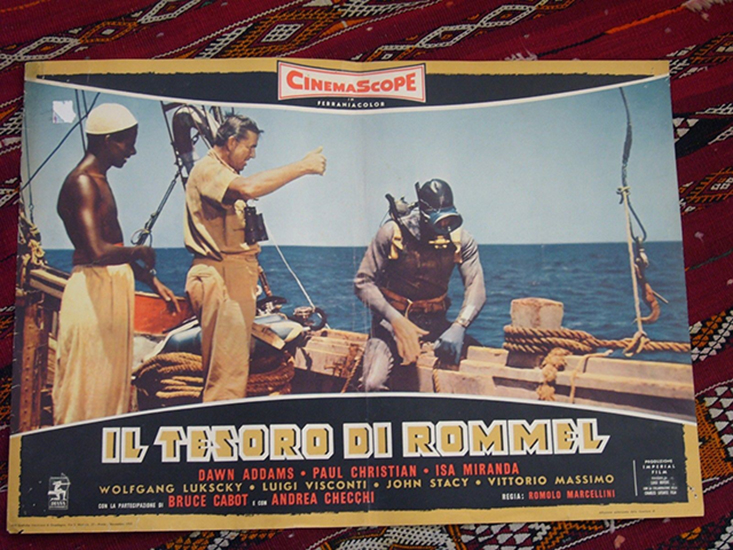

Another great opportunity for the advertising launch of the new Acquasub SCUBA unit was due to the film "The Treasure of Rommel" by director Romolo Marcellini (see Figure 30) lauched in Italian cinemas on December 22, 1955. This film, which saw how main protagonists the actors Dawn Addams, Isa Miranda, Paul Hubschmid, Bruce Cabot and Andrea Checchi, could count, as underwater filming consult, on the great Hans Hass who called, as main stunts during the underwater scenes, in addition to Raimondo Bucher also Silverio Zecca , fresh off the expedition to the Red Sea.

In this film, Salvas still supplied all the diving equipment exclusively, as had happened with the Sixth Continent. Unfortunately, however, the film was not very successful and therefore the advertising returns of this operation were modest.

|

| fig. 30 |

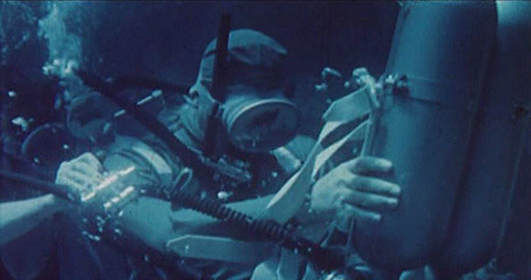

Some of the scenes in the film in which the Acquasub SCUBA unit can be seen are shown in Figure 31 and Figure 32.

|

|

| fig. 31 | fig. 32 |

The entry on the market of this new model, officially in production since 1954, did not leave indifferent the main Italian competitor of Salvas, namely Pirelli which already in the following year, 1955, presented its own SCUBA unit called "Tricheco" (see Figure 33 and Figure 34).

|

|

| fig. 33 | fig. 34 |

Unlike Salvas which, despite some attempts to develop a model of its own invention, in the end selected the Cousteau-Gagnan production formula on license, Pirelli preferred a completely Italian solution. The Tricheco was in fact conceived, designed and patented by Roberto Galeazzi, a well-known name especially in the field of equipment for commercial diving and for the recovery of sunken wrecks. As you can see, this device was also offered with the full-face mask, which at the time was considered a standard especially for professional applications.

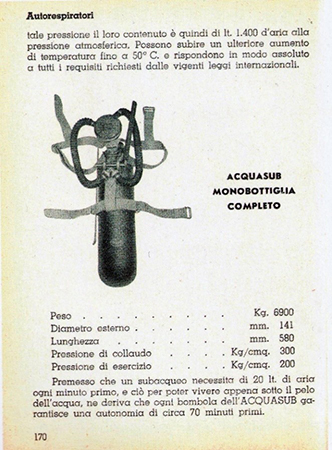

It will then be necessary to wait until 1958 to see other national attempts by Pirelli itself, with the famous Explorer (see Figure 35 and Figure 36), by Cirio from Turin with the Super Abissal distributed by Tigullio starting from the same year (see Figure 37 and Figure 38) and finally by Mares with the Air King, released in 1959 (see Figure 39 and Figure 40).

|

|

| fig. 35 | fig. 36 |

However, despite all these outgoing models and the growing interest of Italian companies in this field, the sale of these SCUBA models struggled to take off and the production numbers of these devices remained very limited, regardless of their performance which remained far from those well superiors that would later bring the legendary Mistral.

|

|

| fig. 37 | fig. 38 |

This revolutionary model which, first, introduced the use of the Venturi effect for the reduction of breathing effort, appeared in Italy in 1956 again as a licensed production by Salvas (see Figure 41).

Unfortunately, however, the Italian market was not yet mature enough to support the production of thousands or tens of thousands of units, as was already happening in the same period in North America. The country was still trying to recover from the disasters left by the Second World War and what would later become the so-called "Italian economic miracle" would occur a few years later, during the 1960s.

|

|

| fig. 39 | fig. 40 |

Only during the first half of the 1960s in Italy the number of scuba divers using the SCUBA begins to grow significantly thanks to the better economic conditions compared to those of the previous decade, the development of summer seaside tourism but also to the increasing diffusion of diving schools (at the time represented by FIPS) on the national territory teaching the safe use of this device.

|

| fig. 41 |

And so also the Acquasub, was soon overcome by its younger brother Mistral in terms of performance, cost, reliability and ease of maintenance. It had the same fate as the competing models that attempted to penetrate the modest and limited Italian sports diving market of the 1950s. From the serial numbers of the very few examples still existing and known in the world, we can deduce that only a few hundred units were built. This model still appears in the 1958 Rex-Hevea catalog (see Figure 42) which confirms the production of this model up to that year, a year which was also the last of the Salvas-La Spirotechnique agreement for the production under license of both the Acquasub and of the Mistral. In fact, starting from the following year (1959), only the Mistral was produced and distributed in Italy by Spiro-Sub, a brand owned by Cressi.

The Acquasub should have had a very limited distribution even in some foreign countries, as can be deduced from the cover of the German magazine "Delphin" of March 1959 in which a female scuba diver equipped with this unit is shown (see Figure 43).

Confirming the very limited number of Acquasub units produced by Salvas, this model is considered by collectors of vintage diving equipment to be one of the rarest ever in the world.

|

|

| fig. 42 | fig. 43 |

______________________